Worth More Than the Minimum

I am often reminded of how fortunate Canadian artists are to labour under our status quo; that is, a national fee schedule that articulates appropriate payment standards. In other national contexts, artists aren’t protected by a framework for best practices. Instead, pay-to-play (where the artist is required to pay for opportunities to exhibit their work) or play-for-free (where the artist receives zero remuneration for exhibiting or presenting) are typical, along with other exploitative models. Thanks to a group of artists who got together in 1968 to challenge the norms of their time CARFAC was established, the fee schedule was created, and national artist-run culture would be forever altered. Since then, the fee schedule has helped artists — and reputable Canadian arts organizations — establish boundaries for healthy working conditions, making a career in the arts possible.

But, nothing is perfect.

In late September 2019, an updated version of the fee schedule was unveiled at CARFAC National’s AGM in Vancouver. Keeping such a document up to date in our quickly shifting world is surely a Sisyphean process, but the new version manages to address contemporary art practices with greater clarity and precision. What it doesn’t accomplish is to adequately spotlight the problematic way that the information it presents is frequently misinterpreted by its users. Whether intentional or merely thoughtless, the common disregard for an aspect of the document points to a larger underlying issue in the arts.

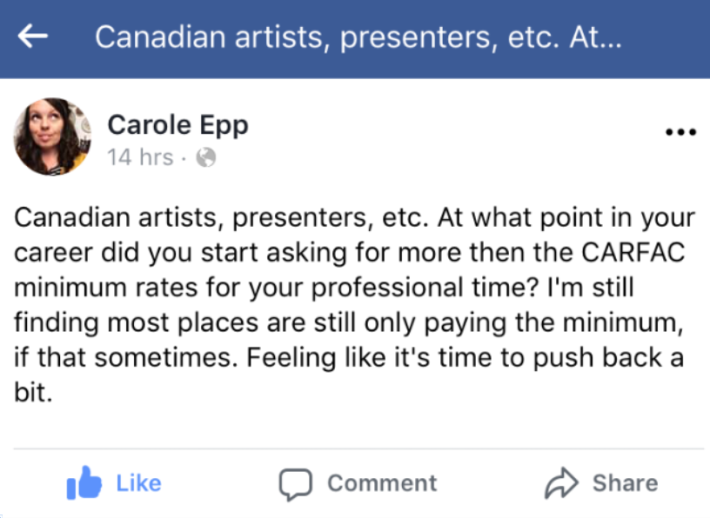

Perhaps it ought to be more emphatically highlighted, but the word “minimum” is an essential and often overlooked detail in the title of the guiding document: the CARFAC-RAAV Minimum Recommended Fee Schedule. Which means that the fees outlined are the absolute minimum that an artist should be paid for their work. But when minimum guidelines are the status quo, as they seem to be, when can artists advocate for more?

Of course, the answers are complicated. The minimum might be suitable when the organization is a low-budget not-for-profit or when artists are at early stages in their careers. But particularly for organizations with higher budgets, profiles, and opportunities, adherence to the minimum is worth questioning. And although length of career doesn’t necessarily equate to increased professionalism or quality of art production, folks who have been working for 10, 20, or 30 years in their field have more than likely acquired knowledge, skills, networks, and expertise that would justify an increase. If the fee schedule is truly upheld as a reflection of professional standards, it may be worth pondering the question: how many electricians, nurses, or teachers are paid at the same rate as they were when their careers began?

Full disclosure: In addition to my studio practice, I’ve been Program and Outreach Director at CARFAC SASK for the past four years. I believe in the work of the organization, both provincially and nationally. Time spent at my “day job” is dedicated to arts advocacy and to supporting the professional development of Saskatchewan artists through mentorship opportunities. I fully embody the organization’s motto — artists working for artists — but I want to be clear that I write this piece as an independent artist, not as a CARFAC representative. Though to be sure, my experiences there have shaped my voice around these issues.

While I’m grateful for the advocacy work of my forebears and my peers, I know that if any status quo lingers long enough, it becomes a problem. The fact that few organizations honour the length and breadth of careers in the arts with appropriate pay is a problem. Even CARFAC SASK is not always able to pay more than the minimum. My beef is not with the fee schedule itself, which does clearly state that “the rates presented in these guidelines are minimum guidelines.” I’m concerned about an overarching issue within arts culture in Canada, where a vicious ouroboros of underfunding is getting us nowhere.

Underfunding is a problem that plagues artists and arts administrators alike. Project and core operational funding at the provincial level haven’t grown significantly in years. Most arts administrators across the country are underpaid and overworked, with salaries that have been stagnant for more than a decade. And if there’s a trickle down effect in this world, the arts industry shows its true nature: the trickle narrows to irregular, malnourishing drops the further down the funding model it goes. The result is that even with steady salaries, benefits, and job security, administrators are exhausted and depleted because the programming output required of them is often not feasible with the available staff and resources. They are hamstrung by limited funds; the minimum fee becomes the norm. Artists become more and more burned out as they stretch to keep their studio practices alive, carry multiple contracts and board commitments, and/or navigate a job that actually pays their bills. Often, contracts for artists require much more work than anticipated, but the fees don’t reflect that reality. Internalized capitalism is activated throughout the industry, and the never ending trickle down cycle is complete — with artists at the bottom of the food chain.

In the years I’ve worked as a professional artist, I’ve been offered the minimum fee without discussion or second thought. Sure, sometimes the minimum is absolutely appropriate and there’s no shame in working for it. But it should never be assumed that the minimum is where an artist values their contributions. There are numerous reasons why an artist might charge more, including but not limited to: they offer high-level professionalism, expertise, or artwork; administrative labour is required on top of the creative duties outlined in a contract; educating a community around what it means to work with an artist is an implicit and burdensome aspect of a project; or simply because they’ll be managing 300 participants in a workshop as opposed to 30. Heavy competition for grant funding and fewer paying opportunities than in other industries mean that artists regularly agree to low pay because it’s better than none. Collectively, artists need to vocalize their worth and say no to any gig that doesn’t respect it.

Simultaneously, arts organizations can take a stance toward ending the unsustainable loop. Leaders should address the imbalanced power dynamic between artists and arts organizations as a first step toward real change in the industry. Start to reinforce the fact that healthy artists are essential to your purpose. Pare back your programming to more accurately reflect the funding you receive and have honest conversations with artists about the value of their work. Advocate to funders for appropriate wages for your staff. Represent the true cost of working in the arts. And while the current political climate increases the precarity of public arts funding, keeping complacent out of fear will not suffice.

I deeply appreciate the public funding that is granted to the arts in Canada. Certainly, other models exist and work in various ways. I believe that the arts are integral to any healthy, evolved society, no less essential than public health, education, and roads and thus, should be funded by government without question. But something is amiss when we are required to be grateful. I wonder if it feeds the general public consensus that the arts aren’t vital? The Saskatchewan Arts Board works for artists and I am always grateful for their support. The thing is, I don’t recall one time when I (or my doctor) had to express gratitude for taxpayer funded healthcare by publicly professing how indebted I am to the Saskatchewan Health Authority.

Change only comes from within. I ask that we all refuse to participate in unsustainable models, and instead, truly value our work and the work of others. It’s a tricky shift to navigate. How many times have you been asked to work for free? How many times have you offered your years of professional experience, access to your networks and acquired knowledge, your technical skills and expertise for low or no pay simply because you believe in the power of art to change the world — or at least to make it a little less abrasive? Artists and arts organizers find ourselves in this conundrum because we are driven to our work for a multitude of reasons, most of them close to our hearts. Obviously, there are times when we give of ourselves for the betterment of ourselves and our communities. But the continual choice to work from a place of passion and generosity without fair compensation is damaging to mental, emotional, and professional well-being. As an old friend once told me, “Too much exposure will kill you.” It’s time that we all find the courage to challenge the status quo and advocate for equitable support for artists and the arts.

Terri Fidelak is an intermedia artist whose work addresses notions of interconnectivity through drawing and illustration, sculpture, installation, and social practice. Fidelak lives and works on Treaty 4 Territory in Regina, Saskatchewan.