Conclusion Part One: The Pandemic Shadow

Once upon a time, without concern, we went indoors and crowded together: to view images and objects in galleries; to hear music in clubs and concert halls; to laugh or weep or be stirred by dramatizations on permanent or makeshift stages; to listen to authors mouth small black strokes on a page into spoken words that built worlds and associations; to watch the human body—expressive, refined, and athletic—dancing on point or bare feet, often airborne; to be transported, over popcorn, into dazzling universes way beyond two dimensional cinematic screens that flickered with light.

The makers of such experiences—artists and presenters—may be among the most resilient and optimistic individuals on the planet. They include musicians, writers, producers, painters, sculptors, glassblowers, actors, comedians, ballerinas, choreographers, composers, and more.

Actors at the Gordon Tootoosis Nīkānīwin Theatre (GTNT) in Saskatoon.

Before 2020, and despite the precarities of the artistic life—creative, economic, personal, and emotional—that were accepted as normal—creators made and presented art, as they’ve been doing year upon year for centuries.

That was once upon. The now of the more than two-year-old pandemic has been—to understate—different.

In conversations with many creators, organizations, and institutions, about that now, I have seen a creeping shadow darkening their spirits. I’ve also witnessed resilience. To investigate the shadow and the light, I set off on a ‘round-up’ of some of the artists and organizations I spoke to early in the pandemic’s onset.

Mario Lepage, the musician and producer known as Ponteix, notes the cancellations that occurred in 2020 just when he “had many tours lined up in Europe and was in the middle of an album promotion.”

Theatre Designer Amberlin Hsu, in Saskatoon, “was depressed for a while…and just trying to survive.”

At Gordon Tootoosis Nīkānīwin Theatre (GTNT) in Saskatoon, Ed Mendez, General Manager, reports on the good and the bad: “At first [Covid shutdowns] allowed us to innovate using new technologies…expanding our reach…The shutdown itself caused significant mental health strain on our staff and the world as a whole, which we continue to feel the effect of today.”

Johanna Bundon in “Untitled Peter Tripp Project” created alongside Jayden Pfeifer & Lee Henderson, August 2021.

Johanna Bundon, an independent artist in dance and theatre, who co-leads Curtain Razors, a small theatre company says, “I continued to train with my dance colleagues over zoom, and in person…Of course, our capacity to adapt and respond to the present moment was put to the test…the realities of the pandemic necessitated shifting gears constantly.”

Laureen Marchand, painter, and entrepreneur in Val Marie, found herself “exhausted” and says: “After these two years… normality had become uncertain, unreliable, distracting, unpredictable.”

The virus and its variants have exposed many ills, besides Covid infections, in society. Along with elders, the immune-compromised, health workers, service workers, and infected individuals, art-makers have been among the most vulnerable and most affected. Artists’ vulnerability is not so much biological as it is economic and cultural-political.

Most artists have one hand in their creative practice and one hand in the gig-economy, where part time work supports their artmaking, to say nothing of providing means to regular meals and a roof.

According to Statistics Canada, Canadian artists earn 44% less than the average Canadian worker, and lack access to social benefits, such as insurance and pension plans, parental and sick leave, and paid vacation time.

Pandemic support mechanisms rolled out by governments and agencies provided, for a while, more financial security than most artists normally feel. Such support—let’s call it investment, as is done with hand-outs to business—was a teaser for what guaranteed income might look like.

Programs like CERB (Canada Emergency Response Benefit) and CEWS (Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy) provided a degree of financial consistency, and for some the ability to explore, create, or redefine, but ease was not guaranteed. Many artists I spoke to mentioned fatigue, depression, fear, lethargy, disruption, loneliness, and burnout. Some rallied quickly, and most kept on creating, regardless. Organizations reflected, reorganized, and many shifted to new presenting modes, often digital.

At the Yorkton Film Festival, Director Randy Goulden reported a pause in their in situ monthly screenings, and a shift to panel discussions presented online. “They worked,” she says, “but were they ideal? Probably not.” And with the Festival’s reliance on the virtual, they could discuss, but could not stream the films nominated for the Golden Sheaf Awards. “We couldn’t put films online,” says Goulden. “We didn’t have the broadcast rights.” Indeed, what is a film festival without films?

Limitations were plentiful, but few in the artistic ecology sunk into stasis.

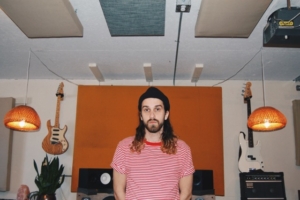

Mario LePage, ‘Ponteix.’ Photo Credit: Stephenie Kuse.

Mario Lepage says that Covid provided new, unplanned opportunities. “We had the chance to create one of the most visually beautiful live performances we’ve ever created, with Saskatchewan collaborators like SCKUSE and Versa Films.” The production was screened virtually. As well, Lepage notes that “many artists came to St. Denis to record music in the studio I humbly named Studio Garage.” He produced music with artists like Shawn Jobin and the folk artist VAERO. He also wrote and recorded his own EP Amélia, released in November 2021.

Amberlin Hsu’s new horizons included learning Japanese and front-end web development. She hopes she might “be able to use these skills once the world becomes healthy.”

At Ness Creek Festival, Manager Carlie Letts

At Ness Creek Festival, Manager Carlie Letts

Moments for Ness Creek in 2019.reports that they are firing up for their twice-postponed thirtieth anniversary festival. “We hope that absence will have made the heart grow fonder and look forward to a wonderful reunion in the boreal forest.” Letts elaborates: “We are still…being cautiously optimistic about the future…We are predicting reduced attendance in 2022 compared to 2019 as we feel that not everyone will be comfortable with larger crowds yet.” And securing services is a challenge. “Many of our food and artisan vendors that had long been a part of our event have had to close their businesses during Covid and are no longer operational.”

Down ‘south’ Josh Haugerud, Manager of the Regina Folk Festivals acknowledged my request for a conversation but was so immersed in planning for this summer that he was unable to make time for an interview. The tasks of planning are more complicated than ever. His labours are directed, most appropriately, to bringing live music to our ears and eyes this summer, and the lineup, released as I was writing this, looks spectacular and includes Buffy Saint-Marie.

Musician Donny Parenteau says of the pandemic, “it was tough as first…it was like learning a new instrument. I opened up my music school to online teaching and started releasing my songs to Canadian radio.” Now he “is pleased to start getting gig offers again.”

“A Spill of Light”, oil on cradled panel; Laureen Marchand

Laureen Marchand describes her experience: “In early April 2021, Darrell Bell, long-time owner of his eponymous gallery and a confidante and supporter of so many Saskatchewan artists, died suddenly and tragically. This set in motion a sequence that led to me opening Grasslands Gallery Online later that year, with support from Creative Saskatchewan. The gallery is a professional commercial art gallery representing some of Saskatchewan’s most interesting artists.” Regarding her own art, Marchand says: “I kept working even though opportunities to show the work weren’t always there…My painting practice has been moving toward new ideas and I’m grateful for that.”

Preliminary StatsCan estimates suggest that nearly all industries in the arts, entertainment and recreation sector, in Covid’s first year, 2020, generated less than half of their pre-pandemic operating revenue.

In 2022, At GTNT, Ed Mendez clutches to hope amidst uncertainty and some despair. “At this point I am attempting to finalize my third Covid-19 related budget and based on how the last two years have gone, I find myself having little faith that we will be in a good place by the time the fall arrives. I desperately hope I’m wrong…The effects of the pandemic have really opened my eyes to how fragile all our systems truly are…If there is one prediction I can make, it’s that it the divisions caused by Covid-19 may take eons to be repaired, if they ever are.” But Mendez is working forward, mustering enthusiasm. “As we tend to say in the theatre world, the show must go on.”

Musician Donny Parenteau in Colours of the Sash concert. 2022

Back to the issue of endemic precarity, particularly for artists. While we await Statistics Canada’s Arts and Culture Data Viewer, which was due in April but seems not to be available yet (as of May 2022), I’ll refer to recent available summaries. Numbers released by StatsCan indicate that well before Covid, in 2017, the direct economic impact of culture industries was $58.9 billion in Canada. And by 2017 metrics, the overall economic impact of the culture industries outpaced that of agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting at $39 billion, accommodation and food services at $46 billion, and sports industries at $7.3 billion. The number of 2017 jobs in the culture industries was 715,400. We’ll have to wait a while yet to know how Covid has affected all those statistics. In the past 12 months (April 2021-April 2022) jobs, part and full-time, in the Information, Culture, and Recreation sectors have been increasing by upwards of twenty percent, nationally and in Saskatchewan, but remain at ten to twenty percent less than they were pre-pandemic. And it is not clear on the Culture category’s contribution to that number. Nor is it clear how many artists are engaged in that cohort.

StatsCan considers culture to include audiovisual and interactive media, visual and applied arts, written and published works, live performance, privately held heritage and library resources, and sound recording, among other components, and doesn’t even factor in the impact of government-run organizations or of education and training in the culture sector.

Money flows, while most artists continue to earn below the poverty line, and their gig economy sidelines are still in recovery. Uncertainty has piled on uncertainty. Industry sources report that as many as one in three arts and culture workers are uncertain about their future in the arts.

It seems that now, with the closing or alteration of many lines of emergency funding (investment) for individual artists, and if Covid fades into memory, that the issue of guaranteed income will be conveniently forgotten too. Miraculously, the resiliency of all who work in the arts continues, and makers and presenters, perhaps without realizing it, are defying the odds.

Randy Goulden, in Yorkton says, “So this year we will be doing an in-person festival and the joy that we’re hearing from our filmmakers, our sponsors, and the public has been overwhelming.”

Johanna Bundon, just becoming aware of the fatigue of the last two years says, “I remain so grateful for each live performance event that occurs.”

Like springtime blooms, venues are open once again, and outdoor presentations appear as weather permits. We makers and consumers of art are cautiously hopeful, seeking a place to show, ready to bump shoulders in audiences, while soaking in rich eye and ear food, and the sparks and shivers of neuronal brain reactivation—experiences that exhilarate and stir joy. Artists continue inventing the once upon a time, in the now that redefines and propels them.

Writer Steven Ross Smith.

Steven Ross Smith is a poet and arts writer. His work has appeared in literary and arts publications across the country in print, audio, video, and digital formats. Over three decades, he crafted the innovative seven-book poetic series fluttertongue. He recently published two chapbooks with Jackpine Press, and his newest book is Glimmer: Short Fictions from Radiant Press. He served as Banff Poet Laureate from 2019-2021. He lives and writes now in Victoria, BC.